Legacy of the Recovery Tree

Resilience based research tells us that how we deal with adversity is more important than the actual traumatic event. We must keep in mind that in general, people are resilient. I’ve seen this in my work with thousands of Holocaust survivors in my thirty years of working with them in the community.

My most significant lessons about resilience have come from my personal and professional experiences with Holocaust survivors. Resilience involves behaviours, thoughts, and actions. Many people exhibited resilient behaviours in the most horrendous circumstances both during the Holocaust and after liberation. During the Holocaust, they maintained their humanity in spite of attempts to dehumanize, humiliate, degrade, and murder them. For example, they helped each other in the camps. Some shared food, encouraged each other to live and not give up, took care of the sick, stood in line for each other on work duty, risked their lives by participating in secret holiday observances, fasted on Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) in spite of extreme hunger and starvation, and so on.

Survivors’ recovery began immediately after the war in the displaced persons’ camps of Europe. Some camps, such as Bergen Belsen, were former concentration camps. In one area bodies were being buried in mass graves, while in other areas activities flourished, just weeks after liberation. Survivors established schools, religious institutions, sports clubs, political parties, cultural activities, and published newspapers. They also married and gave birth to a new generation.

As survivors immigrated to countries around the world, the majority became productive members of the communities in which they settled. They took charge of their recovery by reinventing themselves and learning new languages, trades, professions, and creating new families and communities. A little known fact about survivors is there are eight Noble Prize winners among them in the areas of peace, chemistry, literature, medicine, and physics. They exhibited an extraordinary resilience and love of family and community. My master’s research at McGill University identified survivors’ contributions to the cultural, educational, religious and institutional development of the Montreal Jewish community. They became shopkeepers, teachers, factory workers, religious and community leaders, writers, and artists.

Today, survivors are parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. Many speak out about human rights violations and insist on safeguards to prevent racism and genocides so future generations learn from their ordeals. They continue to bear witness by speaking to groups about their experiences. They take nothing for granted and cherish their relationships. Among the things they hold important are family, friends, health, and a refrigerator filled with food.

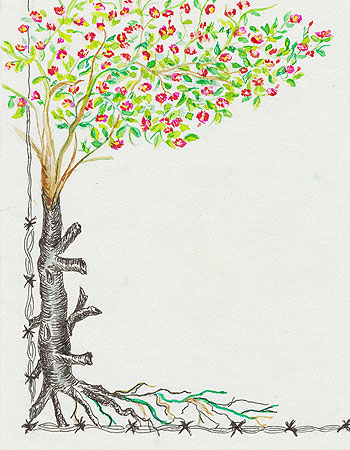

The late artist Suzana Kohn is one such survivor from Yugoslavia. She emerged from Auschwitz to rebuild her life. Her story appears in the book Preserving Our Memories: Passing on the Legacy, a memoir project of the Drop-in Centre for Holocaust Survivors at the Cummings Jewish Centre for Seniors. In it, she says, “Actually I’m a great-grandmother for the sixth time, which would leave Hitler turning in his grave!” She drew the Recovery Tree as part of this group memoir project.

I observe that Holocaust survivors pass on an important legacy to survivors of traumatic life events. As people who have seen the dark side of humanity, they demonstrate by example that human beings are resilient and adapt, persevere, rebuild and recover, during and in the aftermath of tragedy– the human spirit lives on. The Recovery Tree reminds us of this inspirational message. It provides hope for anyone who is experiencing a traumatic life event or challenge.